Good Night

Take a second and think about a door. One moment it separates two places, the next it joins them… And unless you’re in a house of leaves or anti-chamber (or a Stanley parable), that second place will probably be different than the first one.

The steady beeping you hear is the sound of me backing a truck full of pseudophilosophical bullshit into this article, but it’s kind of apt.

Any haunted house story will be influenced by the walls and fixtures that frame it, and the events that took place there. Consider how The Shining is defined by its setting, the Overlook Hotel. It’s a gigantic building with hundreds of identical and anonymous rooms, each holding a new horror. Contrast that with The Haunting, where a smaller house coincides with a series of more intimate tragedies centered around one ill-fated family.

Games excel at imitating the notion of physical space, and for a good long while they were fixated on it. You ran from screen to screen and room to room until you ran out of mans. Mazes were the order of the day in games like Berzerk, Pac Man, and (yeop!) Haunted House.

But in a horror game, the fear of the unknown can make every thrust into the darkness an opportunity for peril. Real magic happens in the spaces between the known and unknown… that moment when your defeated foes are behind you and a door to some fresh new hell is in front of you.

Sweet Home put that door there, and created a genre.

Devil in Her Heart

Sweet Home opens with a distant shot of a five-person documentary film crew traveling to the secluded mansion of the deceased artist Ichiro Mamiya. Their mission is to capture images of his frescoes before the mansion collapses. Before they can get too far, the ghost of a mysterious woman uses her spooky powers to seal them, so she can mete out their punishment for trespassing.

Sweet Home opens with a distant shot of a five-person documentary film crew traveling to the secluded mansion of the deceased artist Ichiro Mamiya. Their mission is to capture images of his frescoes before the mansion collapses. Before they can get too far, the ghost of a mysterious woman uses her spooky powers to seal them, so she can mete out their punishment for trespassing.

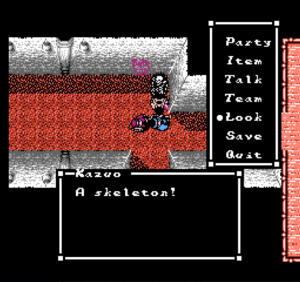

Kazuo, Akiko, Taro, Asuka, and Emi each have a unique tool and varying abilities in combat, and it’s up to you to guide them through the Mamiya mansion’s wings and halls, keeping each alive so you can progress. Kazuo can use his lighter to burn ropes, while Taro and Asuka team up on fresco duty. Emi has the key, and Akiko’s medkit will scare off status effects.

With a handful of exceptions, Sweet Home eschews direct narrative, opting instead to reveal the mansion’s secrets through diaries, notes scrawled in blood on the walls, and in hidden messages on the frescoes themselves.

Wait just one minute… Multiple characters with unique abilities. Narrative exposed through apocalyptic logs. Limited inventory space and environmental puzzles. Multiple endings. Developed by Capcom. A door opening animation!? If I didn’t know better, and if there wasn’t already a game called that, I’d call this Resident Evil Zero.

That’s an astute observation, Me, because Resident Evil began its life as a 3D remake of Sweet Home. For reasons I can’t discern, Capcom decided to go with a biological threat in RE, rather than a supernatural one… but they kept several elements from its predecessor.

If I were prone to wild speculation, I would say they shifted away from the Sweet Home story because the Famicom Sweet Home game was developed and released alongside a movie with the same name and story. That’s right, this is a licensed game. Which would probably make for tricky legal maneuvering if they tried to release it in the States… a shore that never saw Sweet Home.

That’s right, English-speaking audiences owe their ability to play Sweet Home to the localization efforts of Gaijin Productions and Suicidal Translations, and their translation is excellent. It’s not merely functional… it maintains an appropriately creepy tone and sells the sorrow and horror of the events that transpire with a gravitas that defies my expectations of what can be conveyed in 8-bit text.

I know I said that maybe Sweet Home was never released in the U.S. because of licensing issues, but I’m totally aware that it was probably because of all the bloody skulls and child murder. Just sayin’.

I Should Have Known Better

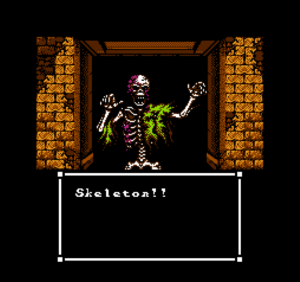

The early hours of Sweet Home are appropriately tense. Do you associate Dragon Quest combat with spooks and frights? You oughta, especially once you realize you’re trying to kill Evil Dolls and swarms of worms with fruit knives (Why couldn’t it have been Pumpkin Demons?).

Random encounters are inherently jolting in any game. They interrupt your progress and drain your resources… but their impact here is compounded by the fact that death is shockingly permanent in Sweet Home. Eventually you gear up and level up, which eliminates most of the anxiety of navigating the rooms. (When you eventually return to the Dining Room at level 17, you realize that those worms ain’t shit). Status effects can still be a drag, especially if Akiko is too far away.

Although you have five people in your team, you can only have a maximum of three people in your party, so Sweet Home is immediately more complex than your bog-standard JRPG. Each party member can only carry two items (excluding their weapon and special item), so inventory management is crucial. Not only do you need to remember what team members are where, but you also need to remember (or write down) where you dropped old items to make room for new items.

Figuring out which items are necessary to navigate the mansion efficiently is the only real challenge to the game after combat becomes trivial. No matter how great the translation is, there’s no intuitive way to discern that the “Bow” isn’t a weapon, but just a longer version of the “Rope” that’s necessary to cross wider gaps. There’s probably a scene in the movie where Kazuo uses a sweet longbow to spear Taro and haul his carcass back to safety, but I lack that cultural context.

If I Fell

The rhythm of Sweet Home has you playing leapfrog with your teams so you can keep them close together. It initially feels repetitive, but you get used to it. That’s not to say it gets “better”.

The rhythm of Sweet Home has you playing leapfrog with your teams so you can keep them close together. It initially feels repetitive, but you get used to it. That’s not to say it gets “better”.

Keeping your teams close is especially important in the early going because the first floor of the mansion is in terrible repair. There’s a limited number of wooden planks that you can find to bridge small gaps, and each plank can only be crossed a limited number of times. Any soul unlucky enough to break a board will cling to the edge with all their might until a teammate comes and rescues them. If you dawdle, bye-bye medkit.

Environmental threats continue to harass you throughout the game, but they’re never as terrifying as when you’re counting your steps, hoping you don’t trap yourself irrevocably in a tough spot.

Another trick that Resident Evil alumni will recognize is that healing items are exceedingly rare, and there are only a finite number of them in the game. This works really well when your enemies are also finite and predictable… but anyone foolish enough to walk in tight circles could theoretically fight an endless number of enemies and end up in a fucked place. This effectively makes walking a finite resource, so shrewd navigation of the halls is a defensive consideration.

In case it’s not abundantly clear that I’m pulling out that cliché about how ~maybe the setting is also a character, mannnnn~, the house itself will attack you at random. Chandeliers and statues will fall and fly at you in what has to be the earliest example of QTEs. These traps are never deadly, but choosing the wrong direction to dodge in (or Praying… like THAT will help) can result in some damage to your dudes.

Honey Don’t

I should probably get down to talking about exactly why Sweet Home is as stunningly successful as it is. I buried the lede a bit by not revealing the full plot up there toward the beginning. That’s because it’s handed out crumb by crumb, leaving you guessing until the shocking moment you find a room full of child skeletons (not skeleton children… those are different) in the basement.

I should probably get down to talking about exactly why Sweet Home is as stunningly successful as it is. I buried the lede a bit by not revealing the full plot up there toward the beginning. That’s because it’s handed out crumb by crumb, leaving you guessing until the shocking moment you find a room full of child skeletons (not skeleton children… those are different) in the basement.

The ghost woman who locked your team in the mansion is Lady Mamiya, who remains bound to this place because she cannot forgive herself for her crimes. Thirty years ago, her baby fell into the mansion’s incinerator. Lady Mamiya attempted (unsuccessfully) to rescue her child, disfiguring herself in the process.

Traumatized by her loss, Mamiya captured other children and burned them, too, to give her child some playmates in the afterlife. Eventually her guilt overtook her and she took her own life, leaving her husband Ichiro behind to grieve, document the haunting, and then disappear mysteriously.

I’ve got no illusions: This is a routine haunted house plot… if it’s not echoed in countless movies in books, then you’ve at least heard rumors similar to it on the playgrounds of your youth. “Bloody Mary” ain’t just a cocktail, y’know? What makes this version of the story so special is the restraint with which it’s told, and how it gives you a role in resolving it.

Everybody is Trying to Be My Baby

First, the restraint. By 1990 we’d seen two Ninja Gaiden games with their cinematic cut scenes. Sweet Home was so tied up with its co-concurrent film that they used footage from it to promote the game. Yet, they left it to the player to piece things together. Prowling through tiny, claustrophobic rooms, you had every incentive to not seek out these bits of extraneous plot. Capcom was confident that they could leave it to the player to investigate and assemble the facts of the matter, and if they missed something… so be it.

First, the restraint. By 1990 we’d seen two Ninja Gaiden games with their cinematic cut scenes. Sweet Home was so tied up with its co-concurrent film that they used footage from it to promote the game. Yet, they left it to the player to piece things together. Prowling through tiny, claustrophobic rooms, you had every incentive to not seek out these bits of extraneous plot. Capcom was confident that they could leave it to the player to investigate and assemble the facts of the matter, and if they missed something… so be it.

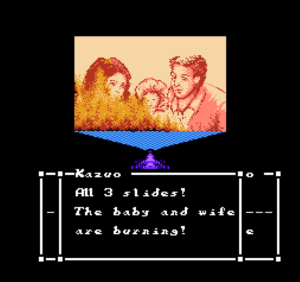

It helps that these bits of story are so constrained by the format. Each message is a few lines long, heavily truncated, and riddled with ellipses. They read like the last utterances of a dying man. Like the great music in this game, the economy of the translation leads to fantastic bits of unintentional minimalist poetry.

Second, the resolution. The last stretch of the game has you assembling a number of items that will prove to Lady Mamiya that she is dead and gone… and that the death of her child wasn’t her fault (The other ones? Yeah, those are her bad).

A lesser game would have you resolve the final battle with sheer force, but your encounter with Lady Mamiya plays out like a puzzle. You must follow the clues that were given to you in the endgame. to present her with evidence that will remind her of her humanity and convince her to move on. A diary to prove her husband loved her, a photo to prove she was once beautiful, a coffin to prove her child has moved on. Then an exorcism, and the house implodes (real original, fellas).

Good Morning

With Sweet Home, we’ve crossed a threshold into games that more closely resemble the Survival Horror we know and love. We have a little while until games of this ilk (minus the turn-based combat) become the norm, but playing this has convinced me that a great deal of what I appreciate about the genre was created, pretty much from whole cloth, right here.

With Sweet Home, we’ve crossed a threshold into games that more closely resemble the Survival Horror we know and love. We have a little while until games of this ilk (minus the turn-based combat) become the norm, but playing this has convinced me that a great deal of what I appreciate about the genre was created, pretty much from whole cloth, right here.

I never really explained the whole “door” thing from the opening of the article.

American audiences will know the “door opening animation” from Resident Evil. It was a really creepy way for Capcom to disguise the loading screens between the pre-rendered rooms of the Spencer mansion. It gave you enough time to wonder why nobody at Umbrella could afford WD-40… and also whether or not you would be decapitated on the other side of this door.

That “door opening” thing showed up here, in Sweet Home. first. Except they weren’t disguising load times. They just wanted to fuck with you.

Survival Horror, dawg.

A Day in the Life

For the second time in a row, I must apologize for how long it took me to post this article. Given that Sweet Home is an unexpected JRPG, my better judgement told me to truncate my play session and post before I beat it. But my best judgement told me that this game was (ahem) sweet, and I needed to beat it no matter what.

Given that none of the next games are Dragon Quest-inspired JRPGs, my hope is that beating them won’t take too long. I’d like to settle on a biweekly release schedule, which seems realistic with some time budgeting. Of course, this could all fall through. Like a dude… through a plank… in a mansion…

The next game is Uninvited for the NES, which I’ve played and covered for Watch Out for Fireballs! in the past couple of years. It’s a short game and the most Lovecrafty of the bunch so far.

I’d really like to hear how I’m doing. Have I introduced you to stuff you didn’t know before? Have you tried old survival horror games because of this blog? Do I sound too needy and insecure? Let me know in the comments, or at kole@duckfeed.tv.

BLA BLAUGH BLAUGH BLAUGH.

Huh?

I love this entry. I’ve loved all the entries, actually.

I haven’t played any of these since you started the blog, but you have given me fond memories of playing Friday the 13th at my cousin’s house. I’m also going to be running a session of the rpg InSpectres based on Sweet Home.

-Russell

I love this entry. I’ve loved all the entries, actually.

I haven’t played any of these since you started the blog, but you have given me fond memories of playing Friday the 13th at my cousin’s house. I’m also going to be running a session of the rpg InSpectres based on Sweet Home.

Just binged on the articles so far, and I really enjoyed them. I have to ask, how committed are you to tackling the games in chronological order? I understand the importance of covering the foundation of the genre before dipping into the more exemplary titles, but I wouldn’t mind reading your thoughts on more modern examples from time to time. Regardless, I like the words you use, so it doesn’t really matter what you cover.

Kole, I love your work and I really like checking out opinions on old games so please keep up the great work!