From Beyond

It’s sick how games trivialize death. Think About It: What if, each time you died in a game, someone died in real life? You should feel terrible about yourself.

Sorry, wrong window. I was working on the script for my new indie game. See, it plays with the established video game tropes that we are used toooooooooooooooo

The treatment of death in games has swung back and forth wildly over the years. Around the time that Uninvited and the other “MacVenture” games by ICOM came out, Sierra Entertainment dominated PC adventure games… and a single false step in those games could kill you on the first screen. They really, really liked death.

Then, in five years’ time, LucasArts declared death dead.

As much as I love the relaxed feel of a Monkey Island or the solitude of a Myst, I’m a complete sucker for a gory description. I struggle to play these death-fetishizing games without constantly seeking out failure, because their developers sunk so much creativity and invention into finding new ways for the player to fail.

That puts Uninvited in a weird place, because it’s hard for something you intentionally seek out over and over again to be scary.

The Strange High House in the Mist

Uninvited begins with a literal collision between the modern world and the magical world. Swerving to evade a shadowy figure in the middle of a misty road, you crash your car into a strange and foreboding mansion (again with the haunted houses!). When you come to, your car is on fire and your older sister is missing.

Your car will blow up within three turns, which makes for a wonderful trial by… umm, yeah. The game is screaming, quite loudly, that death is possible on the first screen, and that you’d best pay attention to what you’re doing. Oh, and you’d better decipher the interface, too, because playing this on the NES turns “point and click” into nudge and click. Controlling a cursor with a d-pad is like playing air hockey with a lead coaster.

Like Zork before it, Uninvited forces you to commit the spoOoOoOky crime of mail tampering to proceed. The letter you read informs you that this home belongs to Master Crowley (get it!?), a magician and sorcerer who lost control of his star pupil, Dracan. Crowley lives at 666 Blackwell Road in the original Macintosh version of the game, but Nintendo cut that out because Tom Hanks was running around in the sewers killing himself and others for Lucifer.

Okay, cool. A wizard has a mailing address. Wait, what? That’s the weird thing about Uninvited: it’s a comedy.

The Evil Clergyman

With Uninvited, we officially wander into H.P. Lovecraft territory. Not the cosmic stuff, but the “strange and magical forces undermining the world of man” stuff. One of Dracan’s diaries explicitly states that he intends to destroy the modern technological world (no, his last name isn’t Durden… I checked). There’s nothing psychological about the horror here… It’s about as Vincent Price as you get. You’ve got the ghost of a dolled up southern belle, a horde of zombies, demons for days, and a giant spider (along with the requisite arachnid anesthetic “Spider Cider”).

If you read Uninvited as a parody of horror standards, it’s great. Not Young Frankenstein great, but still pretty great.

In the Watch Out for Fireballs! episode about the MacVenture games, we talked about “item chaff”, which is when useless items outnumber useful items. The net effect of item chaff is that you wander throughout the mansion in Uninvited amassing an extensive collection of towels. After Towels 1, 2, 3… and then again after Towels 17 and 18, I began to suspect that being an adventure-game Roomba wasn’t the best strategy… but I held out hope that there would be a Lemonade Stand-esque minigame where the protagonist and Crowley open up a Bed Bath and Beyond (with an emphasis on the “Beyond”).

Maybe ROM hackers can make this happen… or at least give me a Bubsy 3D-like tribute sequel in this vein. Get on it, indie horror devs.

The Picture in the House

There’s a balance to be struck in determining what’s grabbable in an adventure game.

If you can only pick up a few items, and each has a purpose, the illusion of the game world is stripped away. This leaves you with a very sparse possibility space where you can see the designer’s intention right away, making the game is boring and easy to solve through brute force.

If only a small percentage of the items you can pick up are useful at all, then you gain world cohesion at the cost of a stupidly huge possibility space. This is fine on its own, since it forces the player to think critically about what their next moves should be.

Item cruft is a very important part of Deja Vu (also by ICOM) since you’re expected to keep track of which items will help clear your name, and which items are potentially incriminating. The final puzzle forces you to ditch the bad evidence before you go to the police. Very cool. But it just doesn’t work here.

There are two reasons why this idea isn’t served well by Uninvited (and maybe even Deja Vu).

Reason B: The interface takes a crap once you have more than 7 items on you… which means you have to page through lists, or dive into sub-lists if any of the items is a container. A goodly portion of your time is spent searching for Bottle2, which you swore you picked up, but all you can find is Bottle1 and Bottle3. Although it’s possible somebody got 2 pigs and labeled one of them “1” and “3”…

Reason A: There’s a logic to the puzzles in Deja Vu. It’s grounded in an (admittedly) exaggerated version of the real world due to its genre. As a supernatural horror game (this is a horror blog, after all) Uninvited leans wholeheartedly into the surreal illogic that’s part and parcel of anything to do with demons and skeletons.

Your average adventure game requires you to borrow a little bit of the creator’s logic. You’ll be far more successful if you can stretch your boundaries of what’s “reasonable” to treat every situation as something that was created with a solution in mind. Uninvited takes this to an absurd extreme, and it totally works.

That halberd isn’t meant to be swung at the horde of zombies. You use it to open a stubborn cookie jar. If you even try to use it elsewhere, you’ll uncapitate yourself.

Ghost or spider got ya down? Dig around the pantry for bottles of “NoGhost” or “Spider Cider”, two concoctions that do exactly what their label implies… just as ACME intended.

Magic exists? Yeop. And we treat spells like reusable items with extremely specific uses, such as “DOLLDOLL” which makes dolls talk, “THUNDEDE” which scares off dogs (but only if there are two of them… one or three and you’re donezo), and “CLOUDISI” which puts a cloud around you.

The cumulative effect is that you have to embrace contrivance with the same gusto that the game does. I’m all about this, but I think this is at odds with the game’s insistence on throwing clutter at you.

Pick complexity, or pick inscrutability. Going with both doesn’t serve you well, especially when you’re hamstrung by your technology.

What the Moon Brings

Even if something is goofy and baffling on the surface, it can have hidden scares that jump out and get ya’. It’s not all chubby imps that love cookies and fruit. It’s not all Scarlett O’Hara-likes with skeleton faces (gentlemen, start your engines… am I right?). Hanging over all of those, subtle at first and overpowering at last, is the presence of a dark magical force that is making you… I guess, love it here?

Every couple of screens, there’s a reminder of your character’s splitting headache. These are far more common in areas of the house that were frequented by Dracan… and they go away once you go deeper into the estate.

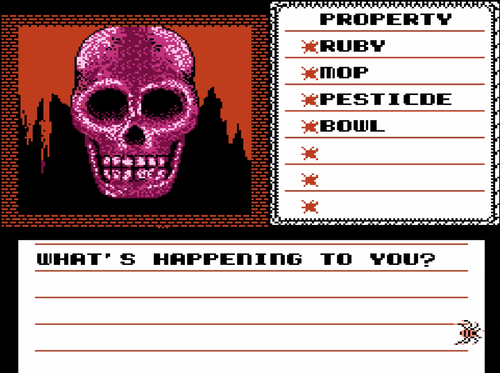

Dracan is sealed away in ice beneath the cathedral, but he is attempting to possess you and force you to do his bidding. This process is aided by a ruby found in an upstairs bedroom… and I get the sense that it was put there as a trap for Adventure Game Roombas. When you have this ruby in your inventory, the game has a time limit… and Uninvited becomes unwinnable very fast.

This is unsettling– if not frustrating– because there’s no indication that the creeping horror is linked to the ruby. In the original Mac version, this “curse” is activated by default, making it a much more difficult game out of the box.

Mean prank or not, this is the closest the game gets to real horror… even in the end when there’s a giant spider AND a flooding room trap straight out of James Bond. A sorcerer who can erode your willpower and make you his pawn is scary no matter what. Maybe the zombie labyrinth was just him selling past the close.

Lovecraft in Brooklyn

As Hex Crank exits the heady Reaganite days of the 80’s and enters the go-go 90’s, games will quickly shift from “heh, that’s a skeleton… spooky” to genuinely upsetting and disturbing things. Sitting down to write this article, I have to admit that I’m really looking forward to that. There’s just more to talk about.

In the opening salvo of this blog, I lay out my case for why horror works so well in video game form. Zooming out to horror in general, I think it speaks especially well to comfortable people who want to borrow a nightmare.

Some people want to escape into something that feels real and immediate, because they’re insulated from anything that could cause them harm. Some people want to escape into a situation that’s more outlandish than the very real horrors they face every day. You know, finances, illness, aging. I’m champing at the bit to write about a game that hits something more profound… because it sucks to borrow a nightmare you could get from a Spencer’s Gifts for $4.99 plus tax and shipping.

Although it’s creepy that your older sister smooches hearts at you in the end credits.