Dungeon crawlers are like tofu or tilapia. They take on the flavor of whatever they’re cooked with. Most of the time you get something with a medieval fantasy bent, but sometimes a developer will throw you a curveball and you end up with something like Shin Megami Tensei: Strange Journey or some of the weird sci-fi elements of the Might and Magic series.

A first glance might convince you that Don’t Go Alone is an example of a dungeon crawler with a twist. However, it’s a re-skin that only goes skin deep, and the efforts taken to make it feel horror-themed don’t conceal the stock standard dungeon crawler the game actually is.

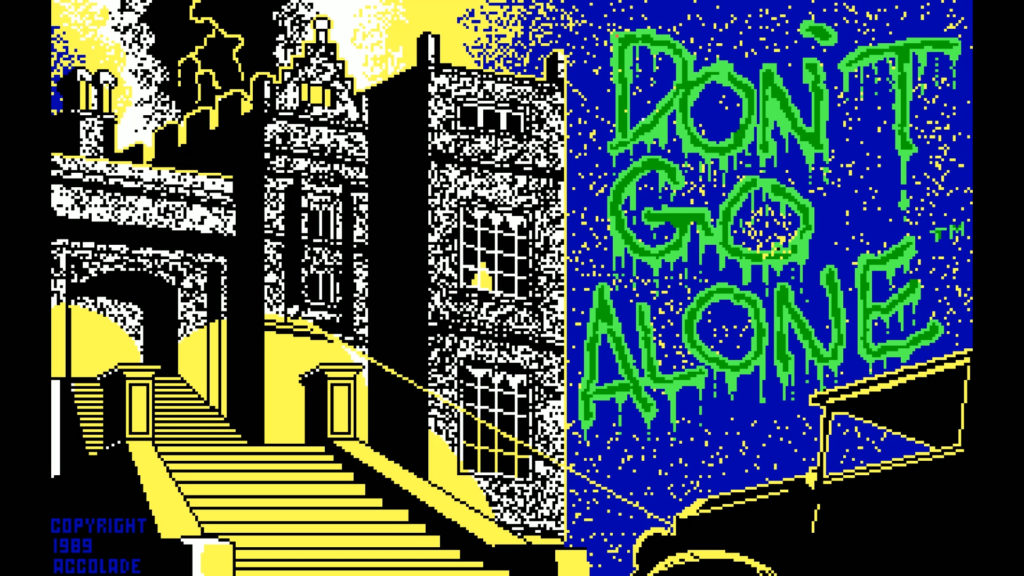

Let’s get the biographicals out of the way. Don’t Go Alone was developed in 1989 for DOS systems by Sterling Silver Software, later known as Polygames. This studio doesn’t have a great pedigree. Though Don’t Go Alone was its first outing, it quickly found itself specializing in making sports games like the early PGA Tour golf titles.

They also had a hand in creating certain versions of Sonic Spinball and Pit Fighter.

Okay, that’s an easy drag. I will stop being intentionally mean. All of this is to say that the horror-themed dungeon crawler really sticks out in their catalogue, which implies that Don’t Go Alone wasn’t a product of interest or passion for moving the genre forward.

Don’t Go Alone takes place in a haunted house which is lorded over by the Ancient One, a demonic presence that drove our main character’s grandfather insane and possessed him. Our mission is one of revenge, to make sure that no one else’s elderly relatives are so debased. So we assemble a crew, and plunge into the heart of darkness, where “dark, dripping secrets abound” (according to the manual)

The manual also assures us that “the walls run hot and cold ectoplasm”, which is convenient.

The last bit of scant story in the manual gives us a revealing, minor assurance. “In this house you don’t die, you merely go stark raving mad.”

The threats we will face in the house’s ten levels won’t physically hurt us, but instead will harm us mentally and spiritually. This detail in addition to the spell casting system (which I will discuss later) make Don’t Go Alone seem like it’s aiming for a Lovecraft vibe where sanity is to be prized over bodily integrity. I’d argue that the nonviolence combined with the game’s very barebones approach to dungeon crawling means it was designed for kids. Very patient kids. The CRPG Addict arrived at the same conclusion.

Don’t Go Alone is a first person dungeon crawler that takes place on a grid, and it features auto-mapping. You’re locked into combat either during random encounters, or when monsters appear at preordained locations. Each floor has a different gimmick, pulled from the same bag of tricks that has built out countless other dungeon crawlers. Things like locked doors, one-way walls, illusory walls, teleporters, dark areas, poisoned areas, etc.

So far, all of this is extremely basic.

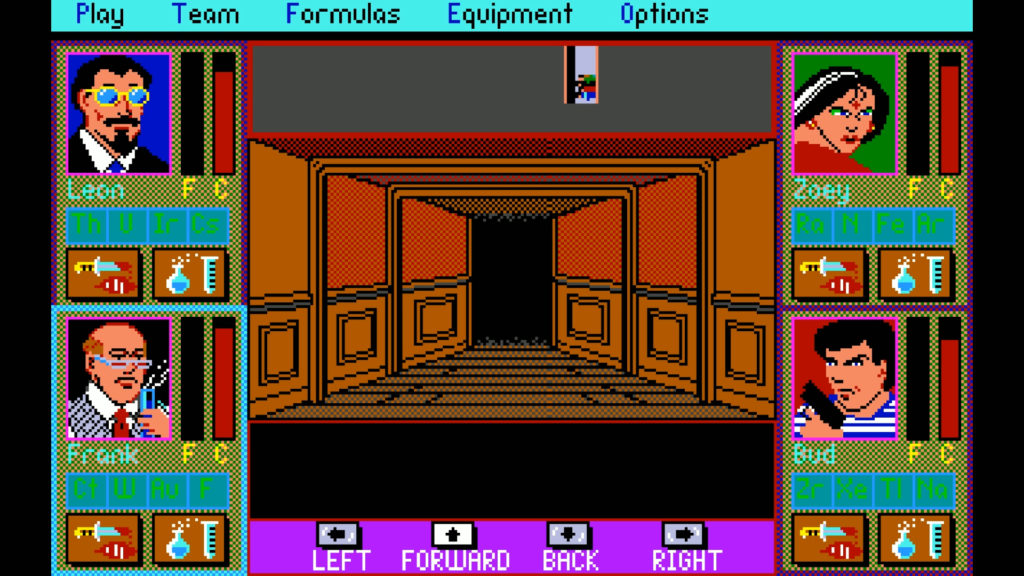

A balanced party contains four specialists, each of which is a proxy for a classic RPG class. Your Adventurer can equip the best weapons and armor. The Technician is less resilient, but can use specialized high-tech weaponry. The Chemist and Mystic both specialize in casting this game’s equivalent of spells, but the Mystic is able to use special items that will deal extra damage to the Ancient One.

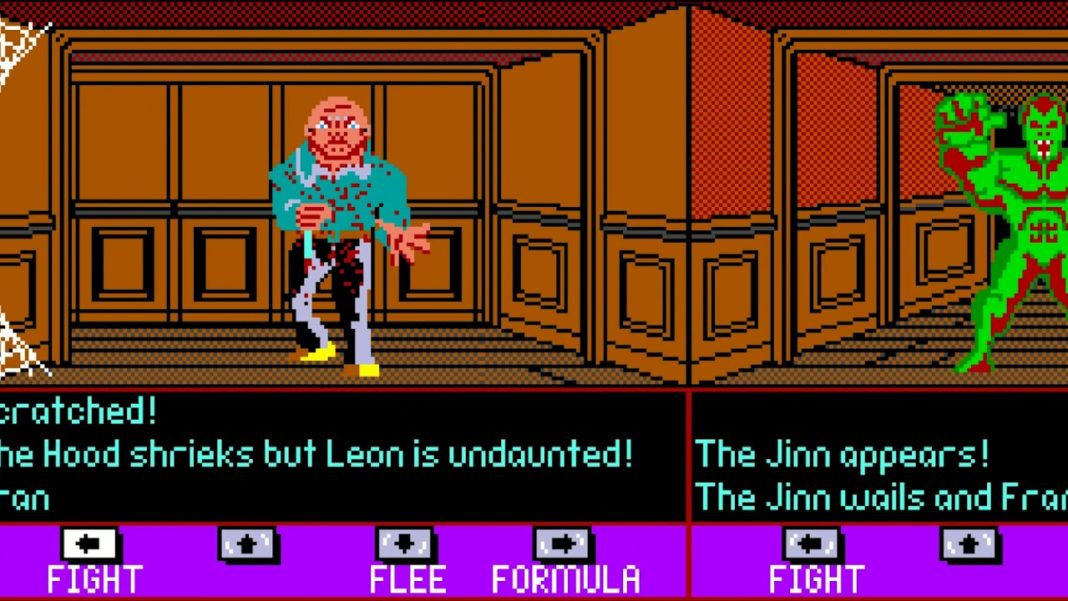

When faced with combat, you can freely switch between your party members and choose your actions in real-time. You can attack with your equipped weapon, fire off a spell (or “formula”), or run. You’re trying to manage your Fear meter and your Concentration meter. Fear is your health, and if the meter gets too high you cannot act anymore. Concentration is your mana, and if it gets too low, you can’t cast any more spells.

Further evidence for this game being aimed at kids is its relatively lenient punishment for losing an encounter. There are two failure states… If you take too long to win, the enemy runs away with a random item from your inventory. This leaves you paging through your inventory menus trying to see if anything vital to progression is gone. If all of your characters get too scared, you pass out and wake up at a random location elsewhere in the dungeon… meaning you’ll need to spend time navigating back to where you were. Possibly from a different floor.

Yeah, I called the game lenient, but both of those options suck the moon out of the sky. I found myself reloading after failing in combat, just to avoid engaging with the penalties the game throw at me. Even if a game doesn’t kill you, you might still wish you’d have died.

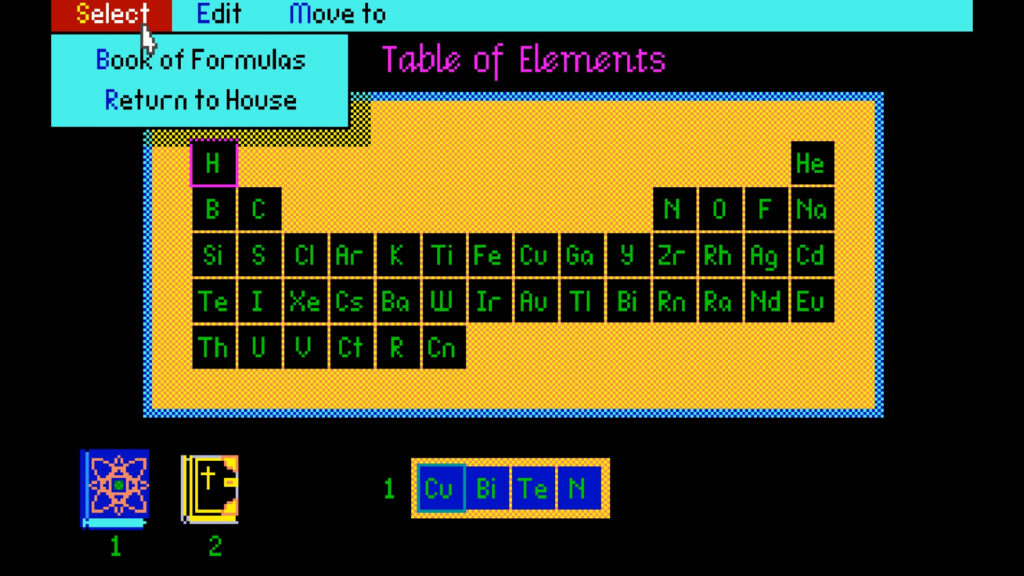

The Formula system is what makes Don’t Go Alone look most unlike its peers, but like other aspects, it’s a very flimsy bit of chrome intended to gussy up some worn out ideas. Because your crew is made up of men (and women) of science, you don’t cast spells. That’s mystical hoo-hah.

Instead, you practice the tested and proven art of alchemy.

Oh.

Every spell is created by mixing chemical elements to produce the desired result. Hearing this, you might imagine an inventive system where knowledge of chemistry lets you solve practical problems in the game world. You might imagine mixing sodium with chlorine to create salt to deal extra damage to slug monsters. Maybe you’d mix hydrogen and chlorine to make acid to dissolve a lock.

With sorrow, I have to tell you that’s not the case (nerd). The actual system is akin to the spellcasting glyphs in Ultima Underworld, except you have access to each component from the beginning of the game. The formulas, however, elude you.

Throughout the game world, you find books containing all of the spells for a specific casting level. If you don’t meet the stat prerequisites, not every formula will reveal itself (components will be blocked out with question marks). If you spoil yourself and construct a formula that’s above your casting level, you either won’t have enough Concentration to cast it, or it will fizzle and waste your Concentration anyway.

Each spell is a stand-in for spells that will seem familiar to fantasy gamers. Direct damage, healing, buffs, debuffs… Although the MVP of my playthrough had to be the map spell (sorry, the Occularium formula).

I was desperate for the Formula system to provide more of a twist, to make this game hew closer to its obvious inspirations from the Call of Cthulhu tabletop game. But it remains a devastatingly straight putt that doesn’t move this game closer to being scary.

Now we can move on and talk about the biggest bummer of all. In my previous retrospective about Project Firestart I gushed about how refreshing it was to have a game that was actually scary, not just superficially borrowing the appearance of horror. I’ve gotten whiplash from Don’t Go Alone’s abrupt reversal of that progress.

Setting a new baseline, it’s not like there’s no theoretical joy to be found in a game that pallette swaps a medieval dungeon for a Victorian haunted house. It’s just that there’s no practical, actual joy to be found in Don’t Go Alone’s specific approach.

Pay attention to the screenshots in the article, or the footage in the video essay. The entire mansion, all ten floors, is done up in the same wood paneling. There’s no attempt made to make the house feel like a place. It’s just brown all the way down. Gallingly, one of the house’s ten levels has the nerve to call itself “The Garden”. With no green to be found, the only evidence of gardendom is the fact that most of the rooms are big and open.

Don’t Go Alone doesn’t just fail to be scary, it fails to make you want to look at it at all. As I played, I found myself looking mostly at the tiny automap at the top of the screen, keeping an eye on the text output panel for hints about what the game is trying to depict (such as breezes that reveal hidden doors, or an indication that a painting might be special).

The lack of environmental variety is somewhat offset by a ridiculous amount of enemy variety. I was consistently amused at the menagerie of Kid Pix beasties Don’t Go Alone threw at me, and seeing more of them was my primary motivation for getting to the next floor. These enemies are hilariously animated, oscillating between two action frames. I’ve excerpted a few of my favorites and made gifs as a bonus for Patrons.

A minor counterpart to the enemy portraits is the variety of goofy items you pick up as loot after fights. One of your earliest weapons presents itself as an extra-large Swiss Army Knife. Not shrunken. Not regular size. EXTRA LARGE.

This surplus of enemy variety is merely cosmetic, like most other good things about Don’t Go Alone. Enemies and player characters can only ever affect each other’s HP count. There are no status effects to be found here. There’s no flavor text. There’s no ontological justification for why any given enemy is encountered in any given location. It’s disappointing.

You make progress in the game by gaining levels and venturing downward into new floors. Each floor introduces a new gimmick, and most floors contain a special area with some kind of trick to it. The first few floors play with traversal, either limiting your progress with locked doors, throwing one-way walls or walkways at you, or (strangely) introducing a floor where 90% of the walls are illusory and can therefore be ignored. Sometimes an area requires you to activate a flashlight, and other areas are cursed in a way that makes causes your characters’ fear meters to spike.

Later floors introduce teleporter traps and teleporter mazes. I have nothing to say about those that would amount to more than incoherent rage snorts, so I won’t dwell on them.

The last act of the game has us backtracking through the dungeon with our new formulas to find five golden keys that will open the pathway to the final level. We also venture into the chambers of four unnamed (and otherwise unmentioned) brothers to get pieces of a formula for “The Shield of Zeus”, a spell that lets us not get insta-killed by the Ancient One.

The tenth and final floor is a sprawling labyrinth littered with Spirit Wands and Spirit Mirrors, special items our Mystics can use to deal significant damage to the final boss. After following arrows on the map which lead to directional clues for a giant teleporter maze, we meet the Ancient One for a perfunctory confrontation that is resolved by using every unfair advantage you’ve accumulated so far.

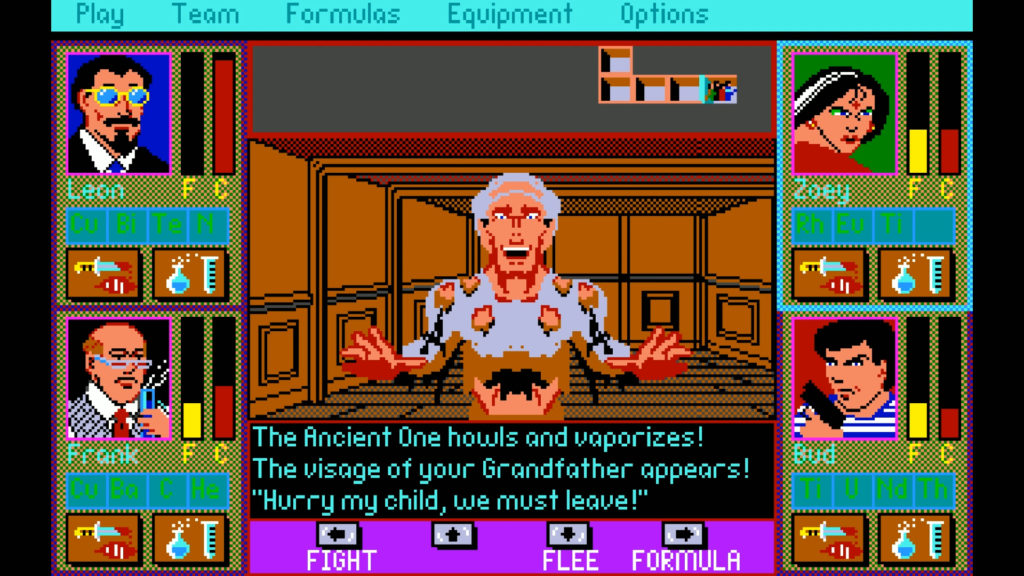

The ending sequence is quite funny. The Ancient One looks like a shaggy wild man, complete with a skull necklace and what appears to be a snazzy leather vest. The killing blow causes the Ancient One to fade away, leaving your dweeby grandpa, combover and all, in his place. He urges your team to flee with him as the house explodes.

The text readout booms a thundering chorus in your name: “You have defeated the Ancient One! Your grandfather is vindicated! Your name will go down in history!”

Then a text box appears, allowing you to undercut all of that. The game asks you: “Do you want to go back into the house?” If you click “No”, you’re dumped back to the DOS prompt. If you click “Yes”, the house reconstitutes itself and you are back at the entrance. The text readout assures you that you hear a menacing laugh.

And that’s Don’t Go Alone, a game that I wanted to find something special in… but I found it wanting instead. As a horror game, it’s as bare-bones as its soundtrack (which lacks music, and only features a few beeps and boops when you attack). Its horror trappings are threadbare.

I’m not a dungeon crawler aficionado. I’ve only recently dipped my toe into some of the better examples of the genre (having first played Ultima Underworld in 2018). Even with those limited credentials, I feel comfortable calling Don’t Go Alone a bland and uninspiring dungeon crawler. Most of its tricks were already cliché before it came out.

So I’m left wondering why the game exists, and what Sterling Silver thought they were accomplishing as they made it. Back when we “covered” it on Abject Suffering, we concluded that there might be something interesting here, but the time allotted and the format of the show wouldn’t allow us to find it. Having revisited it, stem to stern, I think we saw pretty much everything it had to offer in that first half hour.

It feels strange to say, but this makes Waxworks feel like a magnum opus.